I’m so excited to have Amy Lynn Green on the blog to give us a peek behind the curtain on how to create relatable characters in historical fiction.

Trust me, not every writer can do this.

And to be fair, maybe some aren’t trying.

I love the three questions she starts with to create her characters.

- “Who is the right person for the story I want to tell?”

- “What about this character will be interesting to readers?”

- “How is the character going to grow?”

Great place to start. And then you need to flesh it out.

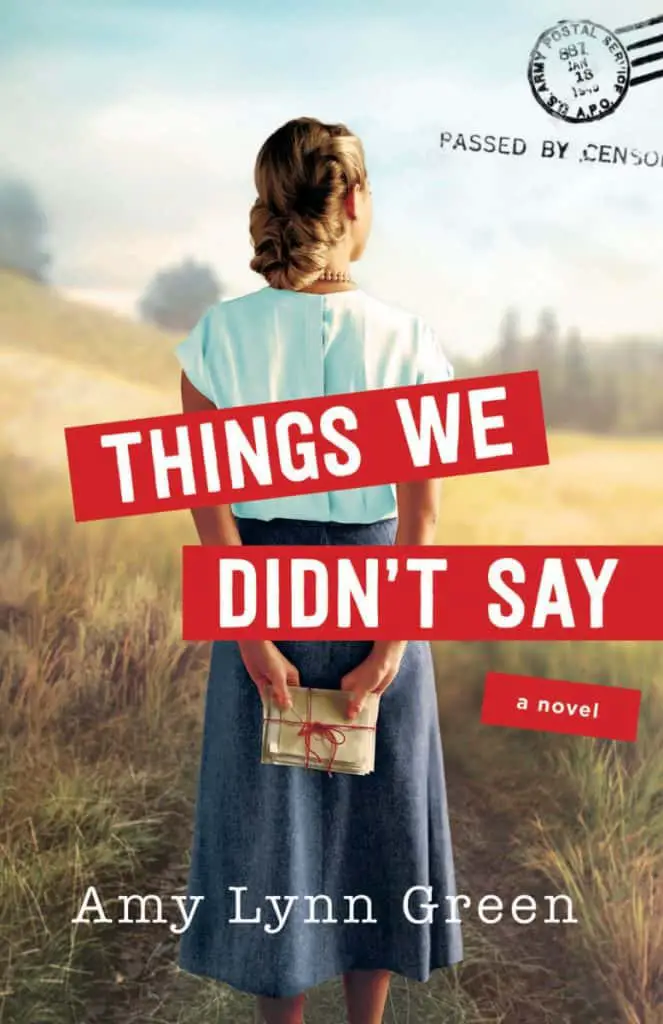

Amy’s book, Things We Didn’t Say, is due to release in November 2020.

The setting is World War II era, but on American soil.

“Johanna Berglund didn’t want to return to her small Midwest town for any reason, and certainly not to become a translator at a German prisoner of war camp. She arrives to find the once-sleepy community exploding with hostility toward the prisoners and those who work at the camp. Her friend Peter Ito, a military intelligence instructor, encourages her to give the town that rejected her a second chance, and as Johanna interacts with the men of the camp and censors their mail, she begins to see the prisoners in a more sympathetic light. But when the men her country is fighting become the men she is fighting for, she must decide who to trust—and whose side she’s truly on.”

I got a sneak peek at the first chapter of Things We Didn’t Say.

Halfway into that first chapter, I connected with Johanna. That rarely happens, especially early on in a story.

It made me curious. Wow. How does an author do that? What’s the secret? So I asked Amy and she agreed to dish to my readers.

*******************************************

Beth wondered if I could answer this writing-related question: “How do you create a relatable character in historical fiction?”

I love this question because it’s so rich with interesting angles. Rather than lump my answer all into one, let’s break it down, shall we?

“How do you”

One thing I always like to start by saying is that every person’s writing process is unique. I’ll be talking about some of the principles and processes I use when creating characters, but my way is by no means the best way, the only way, or the right way for you. For example, I know authors who create characters by:

- Filling out detailed questionnaires about their appearance, personality, and history

- Finding inspiration with photos that have the right look for their characters

- Having a mock interview with their leads to learn more about them

- Following a story structure outline that maps characters’ goals and fears

- Using personality tests like Myers Briggs to make sure they vary the types of characters they use

Any of those methods may work for you. That said, there’s a lot to be learned by eavesdropping on another writer’s process. The steps I go through might help you, but even if they don’t, there are some great general principles to get you thinking.

“Create a relatable character”

When I think back to some of my favorite books, sure, there are some times when I said, “This person is just like me!” Anne of Green Gables, for one, or Samwise Gamgee. More often, I’ve thought, “I wish I could be like that person,” like Inspector Gamache in Louise Penny’s mystery series or John Ames from Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Occasionally, I’ve been hooked by a story even when I didn’t think I’d personally get along with the protagonist if we actually knew each other, like with Sherlock Holmes.

So when I think of making a character relatable, I don’t try to craft a blank-slate everyman/woman who will be universally adored.

Question One

I usually start with “Who is the right person for the story I want to tell?” While I’m not even close to a detailed outliner, I often have a central theme or plot point I know my novel is moving toward, or at least an idea of where the story begins. With that in mind, I decide on a general type of person, like a HR manager hiring someone for the job.

Only…I look for someone totally unqualified for the task in front of him or her.

In Things We Didn’t Say, I knew my story would be about a translator who had the delicate task of maintaining strained relationships between German prisoners of war and residents of a small Minnesota town who did not want them there.

So, I described Johanna Berglund, a brilliant language prodigy who A. had burned a lot of bridges with people in her small town, B. was blunt and self-described as “terrible with people,” and C. wanted to get away to Oxford as soon as possible.

See? Lots of potential for conflict. At this point, I’m just taking big-picture notes, not getting down to the details unless the details hook into the plot in some way.

Question Two

Once I have a general profile of my character, I move on to “What about this character will be interesting to readers?” Some of that might already be in place, but here’s where I develop things like the character’s…

Relationships: Sometimes they’re complicated (the former best friend with an unaddressed grudge), sometimes they’re supportive (a father who’s willing to sacrifice his political future to stand by his family), sometimes they’re downright hostile (the newspaper editor actively looking for dirt and rumors). A mix of all three is usually good.

Personality and Values: These are more tied together than you might think. We act out our values. Introverts often value deep conversation and alone time. The class clown values attention. The detailed micromanager values organization and efficiency. And so on. I like to jot these down in connecting columns. In Things We Didn’t Say, Jo has always felt a little lonely and left out, so she cares about underdogs, defending and befriending them despite her tough exterior.

Dialogue: This includes sense of humor (dry wit, exaggerated sarcasm, self-deprecating whimsy?), speech quirks (analogies, education level, regional dialect), and sentence length (wordy or concise?). I once heard that if you have a somewhat unlikeable character at the start (and Jo has a strong personality, so I worried about that), be sure to make them funny. So that’s what I did.

Backstory: Sometimes this fits into other categories, but we want to understand why the character acts the way she does, or why he looks at the world in a particular way. Past life experiences help with that. For Jo, I included an unrequited romance with the pastor’s son right after Pearl Harbor, who then died in the war to explain her reluctance to risk loving others and her faltering faith.

Passions and Hobbies: All of the character’s dreams and hopes for the future and what makes them get out of bed in the morning are obviously the most driving, but even minor talents and quirks can set a character apart or give them relevant skills in a time of crisis. For Jo, this includes referencing nerdy classical literature, writing footnotes in her letters, knowing nothing about sports, and participating in her father’s made-up holiday Thawing Day.

Fears: Often, these are the most interesting and relatable aspect of a character to readers. They also give you as an author a great idea of how to exploit your character’s personality for plot drama. Jo lives for being competent and in control…so, of course, I put her in a place where she is personally responsible for disaster she never saw coming. And then gets thrown in prison.

(See how each category adds one more relatability aspect to the character? It’s word magic, I tell you!)

To be honest, for me, some of this comes in the edits. I always read over a draft at least twice with just the main character in mind, trying to make sure he or she is consistent. Does his level of education match how long his sentences are? Can you see her supposed personality flaw come out every time she’s under pressure and not just when it matters to the plot? Have I given him enough interesting aspects, or does the sidekick upstage him in every scene? Attention to those details really pays off.

Question Three

Finally, I end with, “How is the character going to grow?” This one is key for me. There have been some characters in others’ books I stared out liking only grudgingly, if at all, but the reason I loved the book by the end is because those characters grew and changed. (Austen’s Emma, for example, or Steris from Brandon Sanderson’s Wax and Wane series.)

On a big picture level, I think about where my character is starting, especially their flaws, weaknesses, and lies they believe. Then, I think about what I want them to learn or how I want them to change.

To be clear: you shouldn’t make your novel a moralizing sermon. But story is driven by change. There’s a huge emotional impact in victory, overcoming, and even taking a small step of growth (or, if you’re writing a tragedy, in loss and the consequences of a person’s choices, see Wuthering Heights or the musical Hamilton).

In Things We Didn’t Say, Jo starts out as a prickly bookworm who has decided that everyone in town misunderstands her and that there’s no use trying to change that. Even though she has a hidden soft spot and a passion for justice, that’s concealed under a sharp wit and a detached determination. She’s brilliant and bold…but also arrogant and selfish.

By the end of the book, she’s realized a number of things, including, most devastatingly, that she’s made some terrible and foolish choices. Her perspective on the importance of friendship has grown, and she’s willing to take risks to care for others. She has a hard-won empathy where before she was full of impatience, and she’s even willing to give her struggling faith another chance.

To me, that’s what makes a character relatable, because even if I’m not a secret wizard or a revenge-seeking daredevil or a brilliant detective, I know what it’s like to wish I could fix a broken relationship, grow out of a bad habit, or conquer a fear. I relate to the overcomers, because I’m on a journey toward overcoming too (even if my odds don’t look great at the moment—it just means I’m mid-story, right?). That’s what I want readers to feel when they walk alongside my characters through my book.

“In Historical Fiction”

Here’s the part I love. My characters, while they share a wide range of universally human experiences and emotions with me, will have a totally different frame of reference and worldview than I do. Because I write WWII fiction currently, I was born about 70-90 years after my characters. Beyond just the window dressing of costuming and slang, if I want them to come across as realistic, I need to make sure they have time period appropriate:

Social Norms (Ex: What was considered polite or rude? How wide was the gap between rich and poor? How did men and women relate to each other in public or in private?)

Values (Ex: How did people view the elderly? How common was church attendance? What did the ‘ideal’ man or woman look like and why?)

Prejudices (Ex: Were certain occupations looked down on? Who was excluded from everyday life and how? What assumptions would people make about someone with a foreign accent?)

Fears (Ex: What major regional, national, or international events would concern people? What change was starting to come that would threaten a way of life? What were the most common causes of death?)

Pop Culture (Ex: What references would a young person make compared to a middle-aged person or an elder? What was popular at the time that’s all but faded from memory now? How did advertisement influence lives at the time?)

But, if I want them to be relatable, I have to keep in mind that my historical stories are being read by a 21st century audience.

To be honest, that part isn’t hard for me. Interesting character traits and situations are universal, but even some of the WWII-specific situations Jo and others wrestled with have application to current day questions. Pastor Sorenson asks the question, “Does ‘love thy neighbor?’ apply to unwanted foreigners?” Peter Ito wonders how to trust a government he felt had betrayed him. And Jo has to decide what she’s willing to risk to stand up against prejudice.

See what I mean? Those situations are about the treatment of Geman POWs and the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, but in another way, they are the same questions we wrestle with today.

As a writer, we all want our characters to connect with our audience—to be memorable, original, and thought-provoking. And I think the best way to do that, whatever steps you take to get there, is to remember the beautiful complexity of the people around you and let that influence your writing.

Let’s go out there and write something amazing!

***************************************

Thanks, Amy!

Have you ever pre-ordered a book, that is to say ordered a book before it’s release date?

As a former bookseller, let me tell you those pre-orders are critical and so easy to do. I wrote a post about it you can read here.

I bring it up now because there’s still time to pre-order Things We Didn’t Say. Don’t miss your chance to order before release.